I journeyed to Kalinchok several times but none compared with the one I did the first time, which, today, has become little short of a memoir.

Consecrated to Goddess Bhagwati Kali, Kalinchok, the Hindu shrine nestles on a soaring bluff 12, 605ft (3,842m) above the sea level. Regarded a holy pilgrimage, the deity hugs a narrow ridge that sharply falls to deep ravines. Lush rolling hills punctuate the southern horizon in an unbroken chain as far as the eyes can travel.

If the north skyline parades an array of snow-capped peaks, the east on the other, towers with the sacred twin-peaked the Gaurishankar (7,134m) and the Melungtse Himal (7,181m).

The early days

Some half a century ago, Kalinchok seemed off-limits to the rest of Nepal. Just the locals of Dolakha, Charikot, and people from nearby villages visited the highland destination to pay their homage. The reason was not far to seek—lack of communication—roads. Dolakha and Charikot were not accessible by road and still fell short of electricity then.

Further, during those days, the foot-trail from Charikot to Kalinchok was no picnic. The narrow trail cut through rugged terrain and climbed steeply for hours on end. The paths were narrow, slippery, and without footholds at no end of places. The switchbacks that cut through the thick forest often vanished into overgrown shrubs. More often than not, people lost their way.

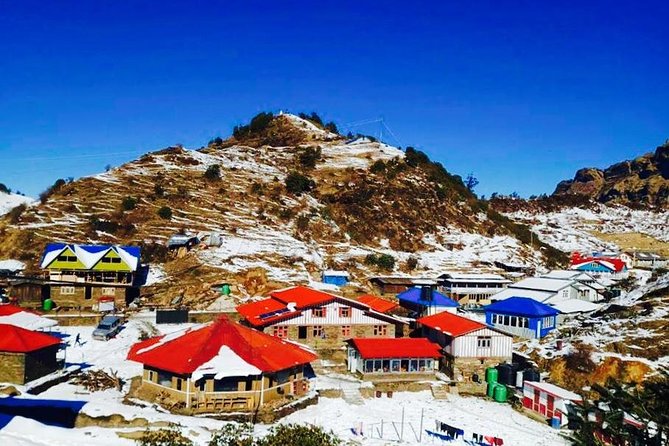

Only clusters of tiny villages lay in the first half of the journey, the rest of the route remained virtually deserted, harsh, cold and unrelenting—nay near frightening. The highlands bore only a handful of shacks belonging to the Sherpa community.

The weather, too, in those heights took a nasty shift at times, and even months like February and March caught hailstones the size of golf balls. At such times, the pilgrims had to face grave danger, as an adequate shelter was difficult to find. What’s more, local gossips ran high that wayfarers were often looted in the dense forest that intercepted the trail.

Only clusters of tiny villages lay in the first half of the journey, the rest of the route remained virtually deserted, harsh, cold and unrelenting—nay near frightening. The highlands bore only a handful of shacks belonging to the Sherpa community.

The weather, too, in those heights took a nasty shift at times, and even months like February and March caught hailstones the size of golf balls. At such times, the pilgrims had to face grave danger, as an adequate shelter was difficult to find. What’s more, local gossips ran high that wayfarers were often looted in the dense forest that intercepted the trail.

Arrival of roads

With the arrival of the Swiss-engineered Lamosanghu-Jiri Road (Pasang Lhamu Rajmarg) in 1985, connecting Charikot and later the dirt road from Charikot to Kuri in 2005, the destination gradually drew more visitors from far and wide including Kathmandu. Most comprised of pilgrims. Others included adventure lovers and odd foreign tourists.

Charikot, 133km northeast of Kathmandu can be reached today by bus. To access the burgeoning town of Charikot, the first leg of the journey takes a four-hour bus ride on the Arniko Highway to Khadi Chaur, Lamo Sanghu. The highway there meets a fork that, after crossing a steel bridge over the Bhote Koshi, follows a narrower feeder road on the right (road to Jiri or Pasang Lhamu Rajmarg), which goes to Charikot. From Khadi Chaur, it takes another two hours to Charikot.

From Charikot, it’s like 18km to Kuri. You can either hire or share with others a Bolero jeep. After Kuri, it’s a one and a half-hour walk up a steep hill with stone steps to climb. A year ago, a cable-car service opened to shuttle the pilgrims to Kalinchok from Kuri.

Charikot, 133km northeast of Kathmandu can be reached today by bus. To access the burgeoning town of Charikot, the first leg of the journey takes a four-hour bus ride on the Arniko Highway to Khadi Chaur, Lamo Sanghu. The highway there meets a fork that, after crossing a steel bridge over the Bhote Koshi, follows a narrower feeder road on the right (road to Jiri or Pasang Lhamu Rajmarg), which goes to Charikot. From Khadi Chaur, it takes another two hours to Charikot.

From Charikot, it’s like 18km to Kuri. You can either hire or share with others a Bolero jeep. After Kuri, it’s a one and a half-hour walk up a steep hill with stone steps to climb. A year ago, a cable-car service opened to shuttle the pilgrims to Kalinchok from Kuri.

Shrouded in mystery

For ages, village folklore and myths abounded the Kalinchok shrine. A mere mention of the deity evoked emotions of awe, dread, and reverence among the native inhabitants of the hill-town Dolakha and nearby villages.

For ages, village folklore and myths abounded the Kalinchok shrine. A mere mention of the deity evoked emotions of awe, dread, and reverence among the native inhabitants of the hill-town Dolakha and nearby villages.

I still recall the words of my mother, a nonagenarian, aged 94 today, when I visited Kalinchok the first time. That was almost 48 years ago. “You better keep those things on your mind. First, do not attempt the shrine the wrong way. There are two approaches—one to gain admittance and the other to exit. The exit comes first but skip that and go a little further to follow the path that climbs to a steel footbridge.”

“Do not,” she continued, “hang around long after the puja. The shrine is visited by all kinds of spirits, some good others evil. Last but not least, do not at any cost return to the shrine after you exit the flight of steps down. You will meet with dire consequences if you do that,” she finished with an admonishing wave of her hand.

She went on to relate the incident when a local villager, disregarding the local belief, went back to collect something he’d left at the deity site. The fellow threw up blood and died after he was back home. That tale gave me the goosebumps.

“Do not,” she continued, “hang around long after the puja. The shrine is visited by all kinds of spirits, some good others evil. Last but not least, do not at any cost return to the shrine after you exit the flight of steps down. You will meet with dire consequences if you do that,” she finished with an admonishing wave of her hand.

She went on to relate the incident when a local villager, disregarding the local belief, went back to collect something he’d left at the deity site. The fellow threw up blood and died after he was back home. That tale gave me the goosebumps.

The old days

I was a strapping youngster, just through with his SLC exams and a freshman at college, when I did my first hike to Kalinchok. I must have been 18 years old then (I’m 67 now). I was visiting my ancestral home in Dolakha for the first time with an uncle. The present Pasang Lhamu Highway was not built at the time. First, I travelled by bus on the Arniko Highway to a roadside town called Barhabishe, located at the banks of the Bhote Koshi River.

From Barhabise, the onwards journey to Dolakha began on foot, a gruelling hike that took a day and a half. The trail traversed across several villages but mostly forested areas crossed our path. We barely ran into wayfarers as the trail seemed deserted with no sign of habitation. We met people only when we neared small settlements.

There were no lodges and teahouses all along the route at the time. So, we had to spend the night in a village. For accommodation, we approached the nearest house and asked the owner. Amusingly, meals for the night depended largely on the owner’s hospitality.

After a day and one night on the trail, we finally arrived at Charikot at around 10 in the morning. “We’re almost home, it’s just four and a half kilometers from here,” announced my uncle. I could not wait to see my hometown.

Dolakha

Unlike Charikot, which happened to be just a cluster of thatched hamlets scattered around the hillside, Dolakha looked flourishing. The village, though small, boasted several shops and a school. As cobbled paths crisscrossed the town, stone spigots seemed to be located on every street. What struck me the most was the presence of Hindu temples and monuments in quite a number. I even saw a Buddhist stupa into the bargain.

I was a strapping youngster, just through with his SLC exams and a freshman at college, when I did my first hike to Kalinchok. I must have been 18 years old then (I’m 67 now). I was visiting my ancestral home in Dolakha for the first time with an uncle. The present Pasang Lhamu Highway was not built at the time. First, I travelled by bus on the Arniko Highway to a roadside town called Barhabishe, located at the banks of the Bhote Koshi River.

From Barhabise, the onwards journey to Dolakha began on foot, a gruelling hike that took a day and a half. The trail traversed across several villages but mostly forested areas crossed our path. We barely ran into wayfarers as the trail seemed deserted with no sign of habitation. We met people only when we neared small settlements.

There were no lodges and teahouses all along the route at the time. So, we had to spend the night in a village. For accommodation, we approached the nearest house and asked the owner. Amusingly, meals for the night depended largely on the owner’s hospitality.

After a day and one night on the trail, we finally arrived at Charikot at around 10 in the morning. “We’re almost home, it’s just four and a half kilometers from here,” announced my uncle. I could not wait to see my hometown.

Dolakha

Unlike Charikot, which happened to be just a cluster of thatched hamlets scattered around the hillside, Dolakha looked flourishing. The village, though small, boasted several shops and a school. As cobbled paths crisscrossed the town, stone spigots seemed to be located on every street. What struck me the most was the presence of Hindu temples and monuments in quite a number. I even saw a Buddhist stupa into the bargain.

I further learned that Dolakha served once as a flourishing Kingdom ruled by the Malla Kings. Little wonder, the modest little village seemed steeped in rich culture and history. The jewel in the crown, the Bhimeswor Shrine, the most revered deity of the Dolakhes, was regarded as the pride and glory of Dolakha. Its fame traveled far and wide and drew devotees by the thousands.

The local people of Dolakha claim that the stone deity at the Bhimeswor shrine perspires preceding any grave national catastrophe befalling the country. Despite repeated wiping, beads of sweat kept trickling down the stone effigy of Bhimeswor prior to the following: the devastating earthquake of 1934 (2007 B.S.), the demise of Panchayat government in 1990, the Royal carnage of June 1, 2001, at the Naryanhity Palace, to cite a few.

The local people of Dolakha claim that the stone deity at the Bhimeswor shrine perspires preceding any grave national catastrophe befalling the country. Despite repeated wiping, beads of sweat kept trickling down the stone effigy of Bhimeswor prior to the following: the devastating earthquake of 1934 (2007 B.S.), the demise of Panchayat government in 1990, the Royal carnage of June 1, 2001, at the Naryanhity Palace, to cite a few.

The ancient trail

After a few days stay at my ancestral home in Dolakha, we were all set to begin the trek, the trail trodden by my ancestors. My anxious grandma hastened to shove into my bag pods of raw garlic and sattu (finely-ground dry-roasted corn), urging me to munch on them when reaching the uplands. “That works against ‘lekh-lagné,” she said.

Lekh lagné translates to altitude sickness. Eating raw garlic and sattu when going to the highlands was a common practice in Dolakha. We hit the trail with my uncle, a cousin from Dolakha, and one village bloke. The first leg of the journey was to Charikot, four and a half kilometers west of Dolakha.

Farming and rearing goats and chickens seemed the distinguishing feature of the village. As we left the settlements behind, the trail led uphill through patches of terraced fields with rice, millet, and mustard. The rice fields were green with tender stalks, waist-high. Other patches had flowering mustard. The hillside seemed to stand out amidst the contrasting colours.

After a few days stay at my ancestral home in Dolakha, we were all set to begin the trek, the trail trodden by my ancestors. My anxious grandma hastened to shove into my bag pods of raw garlic and sattu (finely-ground dry-roasted corn), urging me to munch on them when reaching the uplands. “That works against ‘lekh-lagné,” she said.

Lekh lagné translates to altitude sickness. Eating raw garlic and sattu when going to the highlands was a common practice in Dolakha. We hit the trail with my uncle, a cousin from Dolakha, and one village bloke. The first leg of the journey was to Charikot, four and a half kilometers west of Dolakha.

Farming and rearing goats and chickens seemed the distinguishing feature of the village. As we left the settlements behind, the trail led uphill through patches of terraced fields with rice, millet, and mustard. The rice fields were green with tender stalks, waist-high. Other patches had flowering mustard. The hillside seemed to stand out amidst the contrasting colours.

Groves of bamboo along the trails were a common sight. Over our shoulders to the south, we could see the receding Charikot drop steeply into unbroken terraces of lush rice fields cascading down to the Tama Koshi River that wound its way across a deep gorge.

After we passed by a cluster of thatched huts at a village called Chhotang, the landscape took a shift. The trail wound up with occasional settlements that crossed our path, but gradually dropped in number as it led across uninhabited terrain and lush woods.

As I laboured on the trail on the inclines, my city mind strayed to the thought that our far-off country locales could be so quiet and remote. The dense cover we intercepted held, temperate to sub-alpine mixed coniferous and deciduous forest, largely blue pine, hemlock, oak, and the ubiquitous rhododendron( Laligurans) and Chimal (white rhododendron).

As I laboured on the trail on the inclines, my city mind strayed to the thought that our far-off country locales could be so quiet and remote. The dense cover we intercepted held, temperate to sub-alpine mixed coniferous and deciduous forest, largely blue pine, hemlock, oak, and the ubiquitous rhododendron( Laligurans) and Chimal (white rhododendron).

The inimitable Sherpas

After a few hours on the remote uphill, we were relieved to see some sign of life. It was a small Sherpa hamlet called Gairi Gaon (2,450m). It consisted of just three shacks. If the north commanded a panoply of peaks in the distance, the mighty-looking Gauri Shankar stood right before our eyes in the east. There was a considerable chill in the weather.

After a few hours on the remote uphill, we were relieved to see some sign of life. It was a small Sherpa hamlet called Gairi Gaon (2,450m). It consisted of just three shacks. If the north commanded a panoply of peaks in the distance, the mighty-looking Gauri Shankar stood right before our eyes in the east. There was a considerable chill in the weather.

The smiling Sherpas were very generous and offered us something to eat. The food included dried yak meat, boiled potatoes (their staple), and the local delicacy, chhurpi (hard cheese made from yak-cow or Chauri milk). Freshly made and soft, the cheese was very appetizing.

The Sherpa ladies were reluctant to accept the money my uncle offered for their hospitality but accepted coyly as we insisted. After Gairi, the higher we climbed, the outback seemed further isolated and wilder.

The Sherpa ladies were reluctant to accept the money my uncle offered for their hospitality but accepted coyly as we insisted. After Gairi, the higher we climbed, the outback seemed further isolated and wilder.

“After Gairi, the trail will be isolated all the way, no habitation, nothing to eat. So, expect nothing,” my uncle said with a smile. Very young as I was, and had never traveled out of the Valley, every moment, since I started for my ancestral home, was a one of its kind. When we stopped for brief respites, I munched on the dry-roasted soybean and maize my grandma had wrapped in a piece of rag and stowed into my bag. It surely worked when I felt the pangs of hunger.

The more we climbed, the harder the trail got as dense shrubs seemed to come in the way. Some even stung as they had sharp spikes. Many a time, I could not help feeling that we were lost. As we climbed further, the pristine backwoods teemed with tall pines in thick rows, which seemed to reach for the skies. No mortals around. Total serenity, complete solitude! Sheer bliss!

In one of my later hikes more than two decades later, the same stretch of the jungle was, to my horror, strewn with logs, many freshly felled, and the old left to decay. It looked the unscrupulous loggers had gone on a rampage. Some of the stumps measured close to three feet in girth. Later, I learned that they were more than 100 years old. All I could do was shake my head helplessly.

Kuri

As we slogged up a small clearing, it seemed the excruciating climb had finally ended. The spot was called the Ganesh Twapper. The trail descended into a small valley. “That,” announced my beaming cousin, “is Kuri, our stop-over for the night.” Darkness fell when we stopped at Kuri.

The meadows were bare of trees. In total darkness, we took shelter for the night in a cave called the teen-tallé-odar (literally a three-tiered cavern). As my uncle and others set about to prepare the evening meal, I lay down spent and starving.

We had to bear everything from home–rice, dal (pulse), vegetables, tea, and needless to say, the pots and pans for cooking. For cooking, we foraged for firewood. At night-time, we found dead logs to burn to fight off the cold. The village bloke had to go quite a distance to fetch them.

Even in early November, the temperature seemed to drop down to below zero at Kuri. For four months, the trail remained closed due to heavy snowfall. “The Sherpas from Gairi, Chothang, and Kuri relocate their dwellings and Yak goths (sheds) to lower climes before the onset of snow each winter,” my uncle explained. He had walked that trail to Kalinchok several times.

The more we climbed, the harder the trail got as dense shrubs seemed to come in the way. Some even stung as they had sharp spikes. Many a time, I could not help feeling that we were lost. As we climbed further, the pristine backwoods teemed with tall pines in thick rows, which seemed to reach for the skies. No mortals around. Total serenity, complete solitude! Sheer bliss!

In one of my later hikes more than two decades later, the same stretch of the jungle was, to my horror, strewn with logs, many freshly felled, and the old left to decay. It looked the unscrupulous loggers had gone on a rampage. Some of the stumps measured close to three feet in girth. Later, I learned that they were more than 100 years old. All I could do was shake my head helplessly.

Kuri

As we slogged up a small clearing, it seemed the excruciating climb had finally ended. The spot was called the Ganesh Twapper. The trail descended into a small valley. “That,” announced my beaming cousin, “is Kuri, our stop-over for the night.” Darkness fell when we stopped at Kuri.

The meadows were bare of trees. In total darkness, we took shelter for the night in a cave called the teen-tallé-odar (literally a three-tiered cavern). As my uncle and others set about to prepare the evening meal, I lay down spent and starving.

We had to bear everything from home–rice, dal (pulse), vegetables, tea, and needless to say, the pots and pans for cooking. For cooking, we foraged for firewood. At night-time, we found dead logs to burn to fight off the cold. The village bloke had to go quite a distance to fetch them.

Even in early November, the temperature seemed to drop down to below zero at Kuri. For four months, the trail remained closed due to heavy snowfall. “The Sherpas from Gairi, Chothang, and Kuri relocate their dwellings and Yak goths (sheds) to lower climes before the onset of snow each winter,” my uncle explained. He had walked that trail to Kalinchok several times.

0 Comments